Last radio contact inside Typhoon Wilma, 320 miles east of Leyte, Philippine Islands, October 26, 1952.

"we are in severe turbulence...near the eye...radar inoperative...attempting low-level fix."

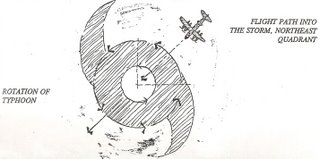

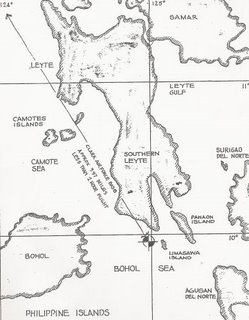

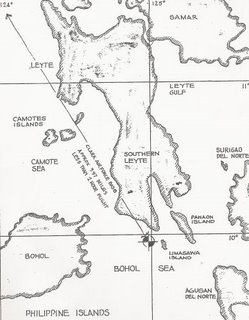

One day, while riding on a train headed for Liverpool, England, I read a letter from daddy. There was something about this letter that caused me to save it for later as I worked on the flight line. Daddy had great penmanship, almost calligraphic in style, but this letter was sloppy, as if it was written in haste. He came right to the point, "Bubba is missing!" on a WB-29 weather reconnaissance aircraft of the 54th Strategic Recon Squadron stationed at Anderson Air Force Base, Guam, Marianas Islands at 3:30 a.m. October 26, 1952 on a 14-hour over-water flight to obtain information about conditions exsting in a typhoon southwest of Guam designated Typhoon Wilma. Upon completion of the flight, the aircraft was to proceed to the Philippine Islands and land at Clark Air Force base, Luzon. During early portions of the flight, radio communication difficulty developed, but this was later remedied. At 8:20 a.m., when approximately 320 miles east of Leyte, Philippine Islands, a weather message was received from the plane. The report stated that the B-29 was in severe turbulence nearing the eye of the typhoon, that the radar had burned out, and that they were descending to obtain a low-level fix. This was the last contact with the aircraft and although immediate search efforts were initiated, the crew was reported missing when the aircraft failed to arrive at Clark Air Force base at 10:00 p.m. October 26, 1952, the estimated time of fuel exhaustion.

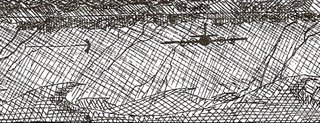

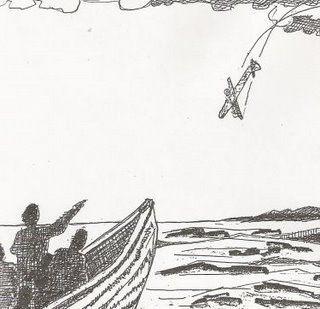

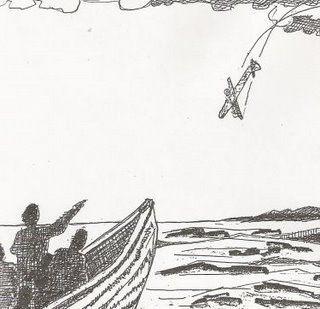

Weather conditions: Reports received during previous penetrations of the typhoon indicated surface winds up to 125 knots, 144 mph, category 5, and that entry into the northwest quadrant at low level would have been extremely hazardous and the sea was phenomenally high and rough. (A category 4 hurricane as measured today is the same intensity as Hurricane Andrew which hit Florida in 1992 or Hurricane Hugo which devastated the Carolinas in 1989). I felt as if someone had yanked out my guts without giving me the mercy of death. A few days later, I received another letter. "Information was received indicating that on October 26, 1952, native fishermen had witnessed a four-engine aircraft plunge into the sea and quickly sink into the water six to eight miles off San Ricardo Point, the southern tip of Leyte Island. Interrogation of the natives revealed that no parachutes were observed and concentrated efforts to recover wreckage or debris in the reported crash area were unavailing. The evidence further reveals that in all probability, the accident occurred off the southern tip of Leyte and that the plane sank intact.

Bubba (Airman First Class Alton Beverly Brewton Jr. AF17279893) and the following other brave airmen were killed:

Major Sterling L. Harrell - Aircraft commander

Captain Donald M. Baird - Weather observer

Captain Frank J. Pollak - Navigator

1st Lt. William D. Burchell - Navigator

1st Lt. Clifton R. Knickmeyer - Pilot

M/Sgt. Edward H. Fontaine - Radio operator

A/1C William Colgan - Flight mechanic/scanner

A/1C Anthony J. Fasullo -Radio operator

A/3C Rodney E. Verrill - Weather equipment operator

In September 1953, Lieutenant General Emment O'Donnell Jr., Deputy Chief of Staff, Air Force Personnel, informed daddy that the nation's highest award of appreciation, "the Accolade," signed by the President of the United States, Dwight David Eisenhower, had been awarded posthumously to Bubba and the other crew members.

Bubba and the crew of the B-29 were never found. We will never know what happened.

Six months later, Bubba was declared dead by the Air Force and a mock funeral was held August 1953 in Detroit by Air Force Personnel Affairs headquarters, 575th Air Defense Group, Selfridge Air Force Base, Michigan.

Bubba was my teacher, my big brother, mentor, and hero. No matter how many years go by, I still find it difficult to say goodbye. It would be unthinkable being black in America without a "Bubba" and I don't have to believe he is dead if I don't want to.