Cookie, Alphonso Jones, Stanley Smith, Pete, Crow, and I formed a gang called the Shotgun Braves. We would hunt rabbits together in the woods near Riverview Gardens outside of St. Louis where our friends Herman, Harry, and Earl Peoples lived. When the rabbit season ended, we would hunt white boys.

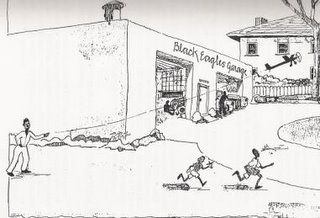

Running fast was a "born with" talent for St. Louis youth in the 40s. We would put on our jackets with the name Shotgun Braves and walk the streets in search of white boys. Some we caught and some we didn't, but those we caught paid the price for the ones we missed. It is amazing to me how the animal instincts and habits could be used by man against man. We would hunt white boys like wolves hunted deer. We would position ourselves about 50 yards apart along Enright Avenue, a street where mostly whites lived. The plan was to chase the white boy as fast as you could within your 50 yards. If he eluded you, the next person would take up the chase for his 50 yards and so forth. Without rest, our prey was usually caught by the second man in the string.

I'll never forget this one kid. He seemed to run faster as a new person picked up the chase. Crow was the next to last person in the chase and he missed. If Stanley, our anchor man, didn't catch him, he would be free. Stanley was within a few yards when, unfortunately for the "prey," he tripped on a flaw in the sidewalk and went tumbling on the pavement. Like wolves, we were upon him.

To further anger the blacks in general, and the Shotgun Braves in particular, in the summer of 1949 the city of St. Louis overnight decided to open the swimming pool at Fairgrounds Park to all races. A few blacks tried to go swimming in the public pool and were savagely beaten with baseball bats. This made headlines in the Post Dispatch. The photographs drove us to new depths of anger.

The Hodiment Trolley had a rather strange route near our house on Delmar. It would run down an alley, make a slow sharp turn, then return to the main street. Where it made the 90-degree turn in the alley, we planned our ambush.

In the summer, the trolley cars were very hot and air conditioning was not part of their equipment, so the passengers would open the windows and rest their arms on the ledge as they traveled along their way. The alley was black and dark and the bright lights inside the trolley made it impossible for the passengers to see us waiting in the dark. We waited with our knives as the trolley slowly negotiated the turn, then we attacked any white arm seeking a cool breeze during that long hot summer. My violent behaviour was governed by memory.

There were a few saloons for white people along Vanderventer Avenue and many times white drunks would use the vacant lot next to our house to sober up. Daddy would ask them to go home many times, but they wouldn't listen. One night, as one was trying to sober up, we offered him this large bottle of "wine." This wine was urine collected from Wilbert, Stanley, Pete, Crow, Booker, and me. He took one large swallow and said, "this is warm and smells like piss." We never saw him again.

Not only were there black vs white confrontations, there were white vs white, and black vs black. You were never safe unless you provided your own protection in your own group, in your own neighborhood. There were many gangs in St. Louis and some of those I remember are the Barracudas, the Crusaders, the High Tops, the Jokers, the Alley Rats (they would throw bricks at you and called the bricks "alley apples"), and of course, the Tin Cans.

During these years, when we weren't gang fighting, we would get on the Vanderventer bus with our shotguns and head for the country to hunt rabbits. Imagine a group of blacks with shotguns and rifles getting on a Seattle bus today. In those days it was legal so long as they were unloaded.

It didn't take us long before we used our skills as model builders to construct .22 caliber zip guns. Stanley took a water pipe and made a 12-gauge shotgun. We would arm ourselves and walk the streets of our neighborhood looking for trouble. One day outside of our neighborhood unarmed, we found trouble aplenty as we left a downtown movie in an area controlled by a gang called the Tin Cans. A group of perhaps twenty boys confronted us near the train station on Market Street about two miles from home. Unarmed and outnumbered, we ran. I ran track in school and I thought I was fast. But Cookie, Alphonso, Stanley, and Crow were out in front. Someone hit me on the head with what felt like a blackjack as I ran into the traffic of Market Street. There was a white policeman standing on the next corner. Cookie, Alphonso, Stanley, and CRow ran past him as he stood leaning against a building. I was in the rear followed closely by the Tin Cans. As I approaced the policeman, I yelled, "We're a long way from home and the Tin Cans are chasing us." He looked at me and said, "You got long legs, nigger, run!" as the gang approached.

Denied a proper education, living with a step-mother I didn't like, chasing gangs, running from gangs, and now denied police protection, I headed for our house and my shotgun. I ran through our front door, past Bubba as he sat in the parlor, ran to my room and got my 20 gauge shotgun, filled my pockets with shells, and headed downstairs. Bubba stood at the door. For the first time in my life, I yelled at my brother. Bubba grabbed me and said that he was going to hold me until daddy got home. I settled down and told Bubba what had happened.

St. Louis at this time was getting on my last nerve. Our step-mother brought into the family a boy who she had raised, Douglas, and I grew to hate her and Douglas because she would play favorites between Douglas, Cookie, and I. Daddy didn't know of these dealings and would always take Douglas' side in any dispute. Once, we were in a second floor bedroom arguing with daddy about Doug and daddy lost his temper and came after me. I ran down the hall and ran out the front door. Daddy was still running after me as I headed up Delmar. I told him that I was running away from home. He told me that if I did to never come back, but those words from my father somehow made me grow up. I walked back to where he was standing and face-to-face told him as soon as I graduated from high school, I was going to join the Air Force and kiss this city called Saint goodbye and that I could take any beating that he wanted to give me, as the rain washed the tears from my eyes. Daddy just stood there as I returned to the house and this ended my delinquent years.